The historical origins of compasses

There is considerable historical evidence that the Chinese were using magnetised compasses as early as 2400BC and that there are records of the use of a magnetised needle around 1120 AD in Zhu Yu’s book.

One of the earliest references to the magnetic compass is by Alexander Neckam (1157-1217) who in his books De utensilibus (On Instruments) and De naturis rerum (On the Natures of Things) written about 1190, refers to what are considered the earliest European references to the use of the magnetised needle as a guide to seamen.

An entry in Encyclopedia Britannica quotes a poem by Guiot de Provins in 1206 referring to a needle touched by an ugly brown stone (lodestone) and floated by stick on water, that points to the Polestar.

Whilst these can all be considered factual, the practicality of using such devices on a ship or even on land is problematic and therein, I suspect, lies the reason why the evolution of the compass appears such a slow process without being attributed to any one specific individual.

The explorer Marco Polo is frequently credited with introducing the compass to Europe on his return. Marco Polo, went to China in 1271 and returned three and a half years later. Marco Polo’s book [1], The Description of the World, has reference to the compass for navigational purposes, but the description is quite vague. Certainly the compass emerges in Europe after he returns from his travels. However I have never seen or heard of any specific reference to material that supports the fact that Marco Polo brought the compass to Europe.

Next is Prince Henry the Navigator of Portugal who has a big impact on navigation at the end of the 13th Century and early 14th Century, but with little evidence of the magnetic compass. All through these times sailors were dependant on the wind and and where it blew them. Christopher Columbus (1451 to 1506) was one of the first mariners to detail the inadequacies of the magnetic compass.

It is not until two voyages in 1699 and 1700 by Edmond Halley (1656 to1742) that a more scientific understanding of the earths magnetic field was made, when Halley issued an Isogonic map of magnetic declination in the Atlantic Ocean.

Move foreward about hundred and fifty years and in an article by Sir William Thomson “Terrestrial Magnetism and the Mariners’s Compass” dated 1874 he attributes the origins of the compass to the Chinese in 2277BC. Sir William Thomson is probably better known as Lord Kelvin.

What we can be confident of is that the compass evolved slowly, and that initially the magnetic properties of the lodestone were useful primarily for divination. Navigation was largely in those early years achieved by staying local, using the stars and the winds not by using mathmatical techniques that required knowledge of direction and courses steered. The compass emerges much later as a useful navigational device, probably around the 12th century in Europe. These events reveal there was a long period of time from when the loadstone was identified to the mid 1550’s when we start to see the compass as a useful instrument. In terms of the process of it’s evolution, the compass is no different to the wheel, both evolved over a long period of time.

This slow progress is supported by the fact that in 1551 there were only 3 Scientific Instrument makers in the British Isles [2], this number rises significantly over the next 300 years to 1851 when it was 837 of which 498 were in London. Looking at Europe, specifically around Nuremberg and the evolution of the Diptych dial in particular it is the mid 1500’s before a magnetic needle is used [3]. Turner [4] states that single needles are found in some sundials of 15th C and by 16th C Navigators compasses use soft iron wire fixed to a card. For me this explains when the compass became seriously involved in navigation.

By the 21st Century the compass has made our lives a lot safer and is still an essential instrument, continuing to be a constant source of fascination and interest to many people. Compass use spans everything from the toy and novelty type device to precise scientific and navigational instruments. Search on the internet for a magnetic compass and you will regularly identify hundreds of items for sale.

Where do all these compasses go once used, who knows? However a few end up in my collection. A majority are invariably well used and yet still work, which I think is a tribute to those who designed and made them. They have frequently survived wars and everyday use, and most at well over 100 plus years of age, are still useable today.

An early compass

The reported history of this compass was that it has been in the same Italian family in Florence for over 300 years. Given it’s construction I am confident that it is pre 1700. However it could be even earlier and was in aprobability adapted and modified over the years.

A lot of what follows is based on discussions with experts in the field – but of course we could be wildly “off course”.

The one thing we know with some accuracy is that the overall diameter is 65mm, height 40mm and compass rose itself is 50 mm in diameter. The case construction would seem to indicate that it sat in a plinth and may well have been designed to be moved from one location to another.

The motif, on the lid, is not unusual on compasses of this period and may have some significance in relation to the original owners.

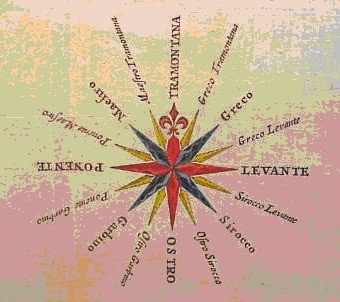

The compass rose and the needle give important clues as to the period when this compass was made. The compass rose is unusual in that not only is it marked with the winds of the Mediterranean, but also the bearing in degrees.

The interesting point is that the lettering styles for the winds and degrees are different and one conclusion is that the numbering was added later than the winds. The sixteen point wind direction system was featured on magnetic compasses from the end of the 15th Century onwards. Could the fact that this is marked with the eight wind system mean this is even earlier than the C15th ?

| Compass Rose Mark | Wind | Approximate Position on Rose |

| T | Tramontana | 020◦ |

| M | Maeriro | 330◦ |

| P | Ponente | 290◦ |

| A | Africus (Libeccio) (Garbino) | 245◦ |

| O | Ostro | 205◦ |

| S | Sirocco | 160◦ |

| L | Levante | 110◦ |

| G | Greco | 065◦ |

The Italians, of this period, associated the north wind with the Tramontana Mountains and this could suggest that the compass was most likely of Italian origin. Some care is needed since an old established Spanish compass manufacturer tells me that the same wind marks were also used at this time in Spain. I think this underlies the point about the slow evolution of the compass, rather than a eureka moment attributable to one individual.

There are two points to note with the needle.

The first is the overall design which suggests that the needle is of quite an early design. Turner [4] states that single needles are found in some sundials of 15th C and by 16th C. He also points out that early compasses were in circular wooden boxes. The second point to note is the cap construction. This construction (the cross bar at right angles to the needle) must have a purpose. A compass manufacturer points out that the compass construction at this time was very pragmatic. Three possibilities exist:

1 to prevent the needle from jumping off the pivot in rough weather.

2 allow the needle to be removed for storage. In early compasses they frequently had several needles for a compass, since the needles tended to loose their magnetism over time.

3 prevent the needle from fouling and damaging the compass rose when the weather is rough.

All are valid, however I suspect that the third one is less likely, since to me, the correct solution would be to put the cross piece in line with the needle to limit the dip of the needle, not at right angles.

Thank-you to everyone who has helped throw some light on this compass.

Acknowledgements

[1] The Description of the World, Marco Polo translated, AC Moule Paul Pelliot Published by George Routledge & Sons Limited, Carter Lane, London 1938

[2] Directory of British Scientific Instrument Makers 1550 – 1851 by Gloria Clifton

[3] The Ivory Sundials of Nuremberg 1500 – 1700 by Penelope Gouk

[4] Scientific Instruments 1500 to 1900 an Introduction by Gerald L E Turner – p34