Sundial compasses are used to tell the time, using the shadow cast by an indicator, also known as a gnomon, onto a surface marked in hours. The origins of sundial compasses are the Nuremberg ivory sundials, circa 16th C and the French Butterfield Dials, late 17th C. The gnomon has to be aligned with the earth’s polar axis and this requires both the Latitude and the direction to be known. This is why Sundial compasses are fitted with a compasses and why they are either marked for a specific latitude or have an adjustable gnomon.

Sundial compasses featured regularly in daily life before about 1830 in the British Isles, telling the local time and were commonly seen on buildings such as churches. However with the evolution of railways and the electric telegraph, they rapidly became redundant. This was because clocks could be synchronised across a country more easily.

In the 18th/19th C the basic design evolved with both fixed and adjustable gnomons mounted on chapter rings.

The sundial compasses with an adjustable gnomon are also known as Equinoctial Sundial Compasses, and can be used at any location, but you need to know the latitude.

The designs were simplified and evolved into the 20th C, with companies like Silva producing a very compact Sun Watch.

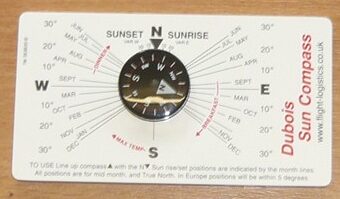

Suncompasses are also used for specific purposes such as photography where it is useful to know where the sun will be during the course of the day.

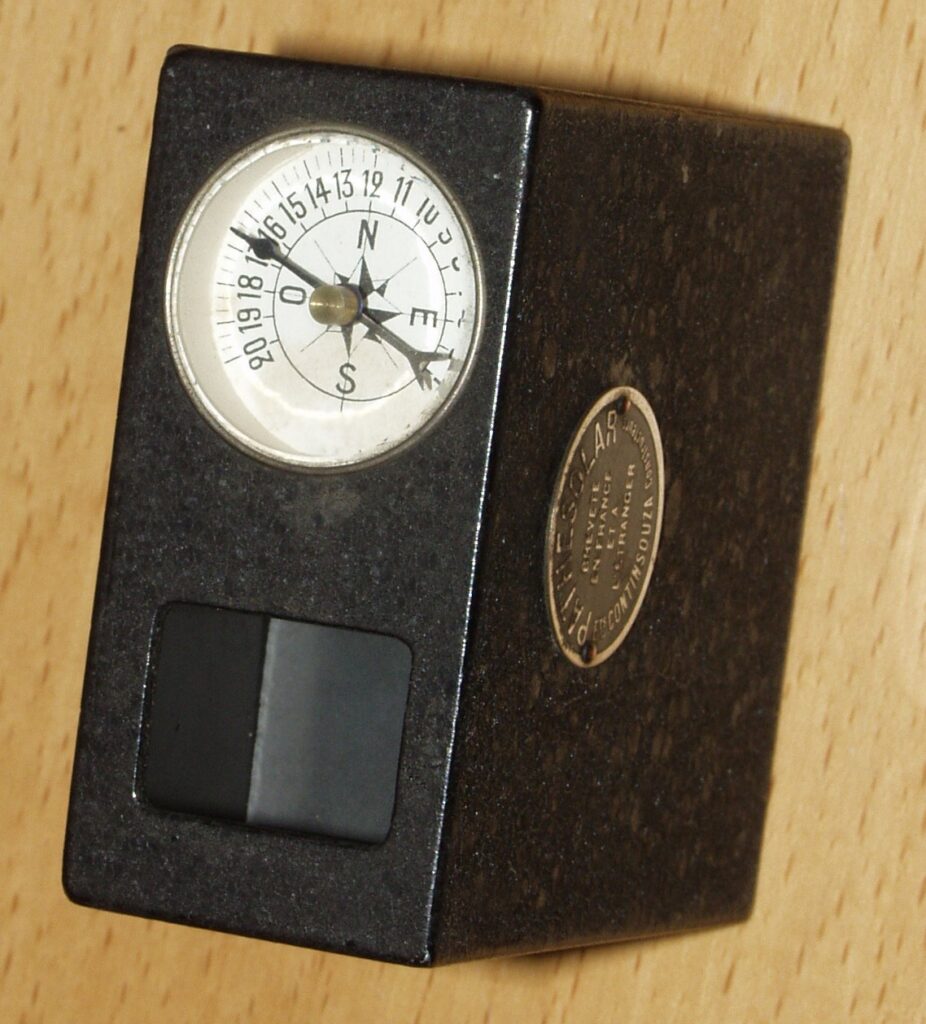

There is a lot of scope for being creative with the design and this is an example of a French Sundial compass, probably mid 20th C.

Useful Resources

Antique Scientific Instruments by Gerard L’E Turner, pub 1980,Blandford Press, 168 pages, ISBN 0 7137 0923 5.

The Ivory Sundials of Nuremberg by Penelope Gouk, pub 1988, The Whipple Museum of History & Science, 144 pages, ISBN 0 906271 03 7. Includes an excellent description of how Sundials work.

Scientific Instruments 1500-1900 – An Introduction by Gerard L’E Turner, pub 1998, Philip Wilson Publishers, 144 pages, ISBN 0 85667 491 5.